The COVID-19 pandemic has given communicators plenty to ponder.

For example… what desired action is ‘stay alert’ meant to convey? Does every slogan really need to have three parts? And is there some secret science behind the constantly changing fonts and colours on Government notices?

So it was intriguing when social psychologist Stephen Reicher, a member of the Independent SAGE group, shared a paper from the science journal Nature explaining the theory behind the Scottish Government’s latest communication campaign.

There are many tactics to change behaviour, such as those highlighted in the EAST framework. So why does the Scottish Government’s campaign focus on encouraging a shared sense of identity and purpose?

Fighting the pandemic requires each of us to make significant changes to our behaviour. Physical distancing. Wearing face coverings. Sacrificing haircuts. We may feel these changes benefit others more than ourselves, and many are difficult to enforce. So how are people persuaded to comply?

While popular culture may suggest otherwise, research suggests people tend to co-operate when facing a serious threat. One reason for this is an emerging sense of shared identity and concern for others, arising from the shared experience of being in a crisis.

Encouraging this shared sense of identity – a sense of ‘us’ – can be a powerful behavioural driver. Here are three campaigns – from the pandemic and elsewhere – that use it to their advantage.

A brighter future is in sight, if we do this right

A shared sense of identity underpins Scotland’s latest campaign, as it eases more of its lockdown restrictions. By using ‘we’ and the #WeAreScotland hashtag, the campaign promotes a sense of unity – of ‘we’re in this together’.

The Stick with it Scotland film delivers a powerful narrative – of progress made, but a job not quite done. The end may be in sight, but everyone still has a role to play in getting there – ‘to stick to it, with all our might’.

What makes the campaign doubly effective is its liberal use of rhyming. Research has discovered that we grasp something more easily if it rhymes. And science also shows that when our brains grasp something more easily, it becomes more persuasive.

Unite Against COVID-19

One country with an impressive pandemic track record is New Zealand, where a national news network survey found 92% of citizens believed the government had handled the crisis appropriately.

Part of that success is undoubtedly down to great leadership. But New Zealand’s communication campaign also impressed with its Unite Against COVID-19 theme.

Used consistently in all its communications, the word ‘Unite’ promotes a sense of togetherness, while COVID-19 is cast as the common enemy.

And low-budget comms played a part too. This simple film featured a range of Kiwi personalities – from All Black rugby stars to film director Taika Waititi– to emphasise the sense of identity and shared struggle.

Don’t Mess with Texas

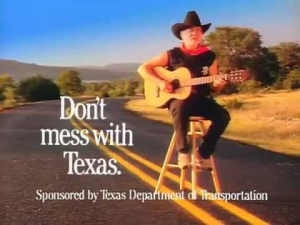

Pandemics aren’t the only situations where identity campaigns can be effective. In their book Made to Stick, Chip and Dan Heath describe the 1980s campaign Don’t Mess with Texas, which had such success in reducing roadside litter that it was still running 30 years later.

Don’t Mess with Texas targeted Americans who ‘weren’t inclined to shed tears at roadside trash’ – young, anti-authority male pick-up drivers, nicknamed ‘Bubba’ by researchers.

A campaign based on self-interest, or protecting other people, was unlikely to work on this audience. Instead, researchers were convinced the best way to change Bubba’s behaviour was to convince him that people like him did not litter.

To do that, they carefully selected famous Texans – football stars, baseball stars, musicians like Willie Nelson – for a series of ads.

And the result? Within a year, visible roadside litter had reduced by 29 percent. After five years, it had dropped by an impressive 72 percent. What’s more, plans to spend $1m on anti-litter enforcement were dropped due to the campaign’s success.

Making shared identity campaigns work

When behaviour change is required for the common good, rather than individual self-interest, focusing on shared identity can be particularly effective. So how can you make it work?

- Work with your leaders

According to the Nature report, people prefer leaders who cultivate, through their actions, a sense that ‘we’re all in this together’. This creates hope and a sense that individuals can make a difference.

But trust plays a major role, which is why dubious trips to Barnard Castle and the like can be so damaging. They create the opposite impression: ‘one rule for us, one rule for them’.

This can have a corrosive effect on messaging. For example, the scientific advisory group SAGE has reportedly advised that the UK Government’s COVID-19 messaging is no longer effective, as trust in ministers has collapsed.

- Use effective role models

Research has consistently found that sources perceived as credible are more persuasive. This becomes even more important when trust in institutions is low, which is why SAGE is now recommending using sports stars, musicians and other celebrities in COVID-19 messaging.

Role models are particularly important at the start of a behaviour change campaign, where new ‘social norms’ have not yet been established.

If you see only one in ten people wearing a face covering in Tesco, you’re unlikely to feel pressure to wear one. But if you regularly see people you respect and trust wearing one, you’re more likely to follow suit.

Even when trust in leaders is high, using role models can still be highly effective, as illustrated by New Zealand’s Unite Against COVID-19 campaign, and Don’t Mess with Texas.

- Highlight positive behaviour

A sense of shared identity can quickly be undermined if people perceive others are acting in their own, rather than the shared, interest. We’ve seen this play out throughout the pandemic, as media stories amplified selfish behaviour – be that panic buying, beach crowding or house parties.

Those negative examples can be countered through facts and positive stories: the proportion of people following the required behaviours, and stories of the sacrifices they’re making in doing so.

Encouraging a shared sense of identity won’t always be successful – and there are obvious dangers in taking it too far, especially at national level. But in cases where behaviour change is critical, and the benefits to individuals may be less obvious, it’s a tactic worth keeping in your comms toolbox.

Dave Wraith for Alive with Ideas