Advances in neuroscience over the last 20 years have revealed intriguing insights into how our brains work.

But neuroscience is a complex field. All that talk of neurons and brain synapses is enough to give anyone a headache. Anything that helps us grasp its relevance for communication can only be a good thing…

Steve Peters’ Chimp Paradox is a simple illustration of our brain mechanics. The older part of the brain – our ‘chimp’ – is the most powerful. It controls emotions, and is concerned primarily with survival. It regards all new information as either a potential threat or a potential reward, and reacts accordingly.

David Rock’s SCARF model highlights five social triggers that are most likely to disturb our chimps. Being aware of these triggers can help us understand reactions to change – both in ourselves and in our audience.

So what are these five areas, and how can we use them to make our communications more effective?

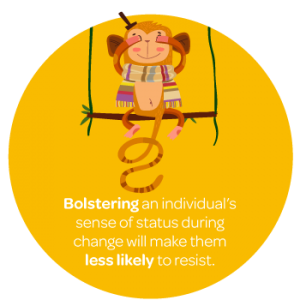

Status

We all have a perception of our relative status in a community or organisation. Work successes, positive performance reviews and great customer feedback can all boost that sense of status.

But threats to our status also come thick and fast. Change, for example, can suggest that long-held skills and behaviours are no longer enough.

We can minimise this threat and instead appeal to our chimps’ sense of reward, by:

- Recognising and celebrating past achievements when starting a major change

- Putting employees in the spotlight by highlighting their specific contributions

- Stressing the continued value of colleagues’ skills and experience, and how they’ll be supported with new training or resources

The more we can bolster individuals’ sense of status during change, the less likely they are to resist.

Certainty

In 1992 researchers looked at the fear levels of test subjects who had been told they’d be receiving an electric shock. They found that people who knew they’d be given a shock – but didn’t know whether it would be mild or intense – displayed more fear than those who knew for sure that they’d receive an intense shock.

Our brains crave certainty, so our chimps see uncertainty as a threat. Communicators often struggle to give colleagues any clarity during times of change. But there are some areas we can focus on: the aims of the change, for example, and the process.

Managers, too, may isolate themselves during change programmes, fearing they have no answers to employees’ questions. We can encourage them to focus on what information they can provide: even if it’s just the ‘known knowns’ and the ‘known unknowns’.

Autonomy

Autonomy is a sense of control over our environment. When we lack autonomy – when being micromanaged, for example – our brains can produce a strong threat response, and our chimps can take over.

Change often takes away people’s sense of control, but we can help mitigate this through our communications.

One way to increase autonomy is to involve employees in the change process as much as possible. Another is to design communications that allow employees to reach their own conclusions: to focus on ‘show’ rather than ‘tell’ techniques.

For example, ‘big picture’ communications are effective because they help employees to explore the need for change themselves and reach their own ‘a-ha’ moments. Storytelling is another powerful technique. As author Hannah Arendt once said, it “reveals meaning without committing the error of defining it”.

Relatedness

Relatedness involves deciding who is ‘in’ or ‘out’ of a social group: whether someone is friend or foe. We all need safe human contact, and this doesn’t disappear when we reach the workplace.

In fact, Hilary Scarlett, author of Neuroscience for Organisational Change, argues that we’ve “hugely underestimated our need for social connection at work”.

Yet, in times of change, our brains often react unhelpfully, and we turn inwards at a time when social connection is most important.

So what can communicators do to influence this?

One way is through leadership behaviour. Influence expert Robert Cialdini shows that when leaders model a strong sense of connection with their people, they reduce this urge to turn inwards. That means encouraging leaders to work closely with their teams, be as open as possible, and encourage questions and feedback.

Another way is simply to engineer opportunities for employees to come together to get shared support – through events, town hall meetings or social media groups. By highlighting that others are going through similar change emotions, communicators can play a significant role in increasing relatedness.

Fairness

Frans de Waal’s TED talk on moral behaviour in animals gives an amusing illustration of how principles of fairness are deeply ingrained in capuchin monkeys.

But of course, it’s not just monkeys who disdain unfairness. Social experiments reveal that most people would rather receive a small monetary reward if they perceive it to be fair, than a higher reward they perceive to be unfair in relation to what other people receive.

A Harvard Business Review article suggests three ways of increasing fairness in the workplace – and communicators can influence all of them:

- Ask for employees’ opinions and give them serious consideration

- Ensure decision making is transparent and consistent

- Clearly explain why a decision was made, and actively listen and empathise with employees’ concerns

Ultimately an employee’s perception of fairness might come down to the outcome of a decision. But we can at least strive to be open, transparent and fair on the processes we use.

If we keep our chimps happy, we tend to thrive, and the SCARF model provides a simple but handy guide to the social triggers that are likely to disturb them.

By keeping these triggers in mind we can design more effective communications to help our audience deal with change.

By Dave Wraith for Alive!